Trail Running After Childbirth: The Importance of Strength Training and a Phased Return

For many women, getting back to running after having a baby is an exciting yet challenging milestone. However, jumping straight back onto the trails without a proper recovery plan can increase the risk of injury, pelvic floor dysfunction, and long-term complications. A structured approach that includes strength training and a phased return to running can optimize recovery, reduce pain, and ensure long-term running success (Blyholder et al., 2017).

Why Strength Training Matters for Postpartum Trail Runners

Trail running demands more from the body than road running—uneven surfaces, variable terrain, and increased impact forces mean postpartum runners need to build stability, strength, and endurance before hitting the trails. Wyatt et al. (2024) found that women who included strength training before returning to running had lower rates of pain and injury.

Strength training helps by:

- Improving pelvic floor and core stability, reducing incontinence and prolapse risk.

- Enhancing muscle balance and joint stability, which is key for navigating uneven terrain.

- Reducing common postpartum issues, such as knee pain and hip instability.

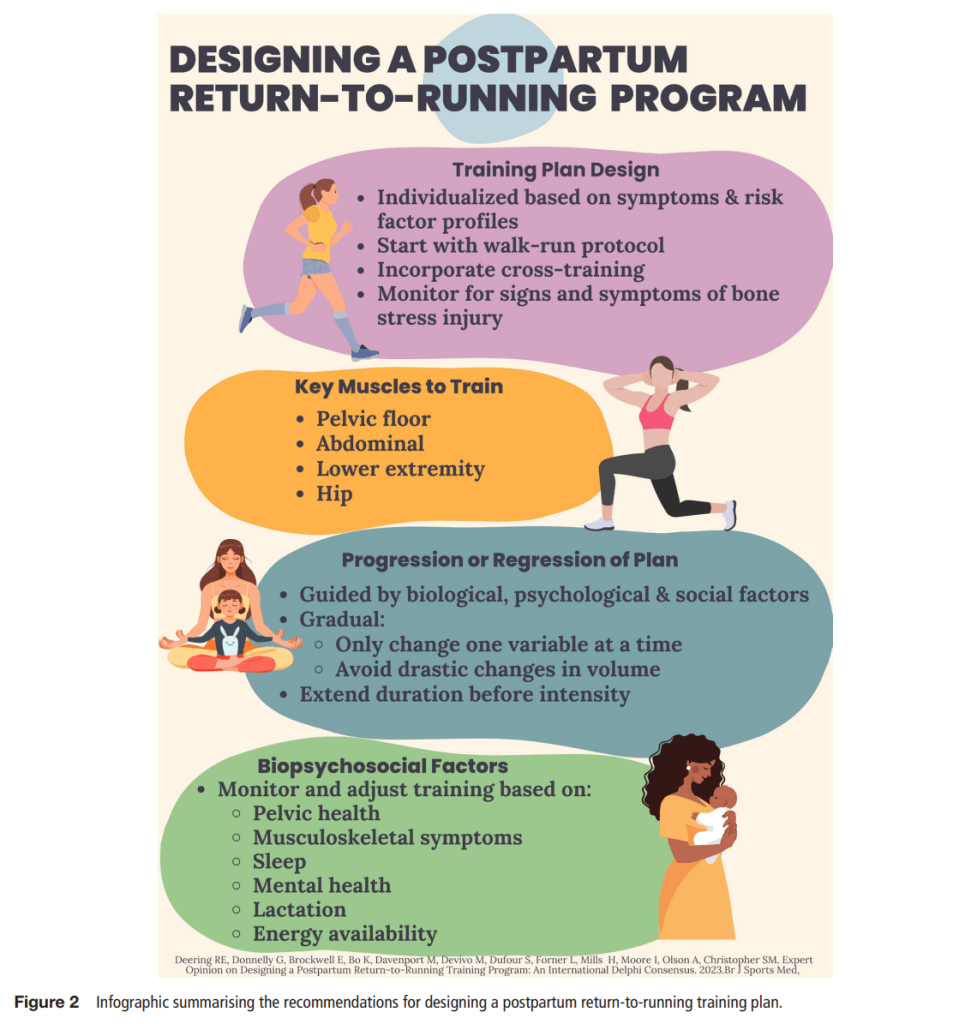

Building a Strong Foundation

A well-rounded postpartum strength routine should include:

- Core strength (planks, deep abdominal activation)

- Lower body strength (lunges, squats, step-ups)

- Pelvic floor training (slow and fast contractions, NHS Squeezy app Home Page – Squeezy)

- Balance and agility work (single-leg exercises, trail-specific drills)

A study of 507 postpartum runners found that those who included weight training had a 48% lower incidence of stress urinary incontinence and 35% less knee pain within six months postpartum (Bø et al., 2017). These benefits make strength work essential for any new mother wanting to return to the trails safely.

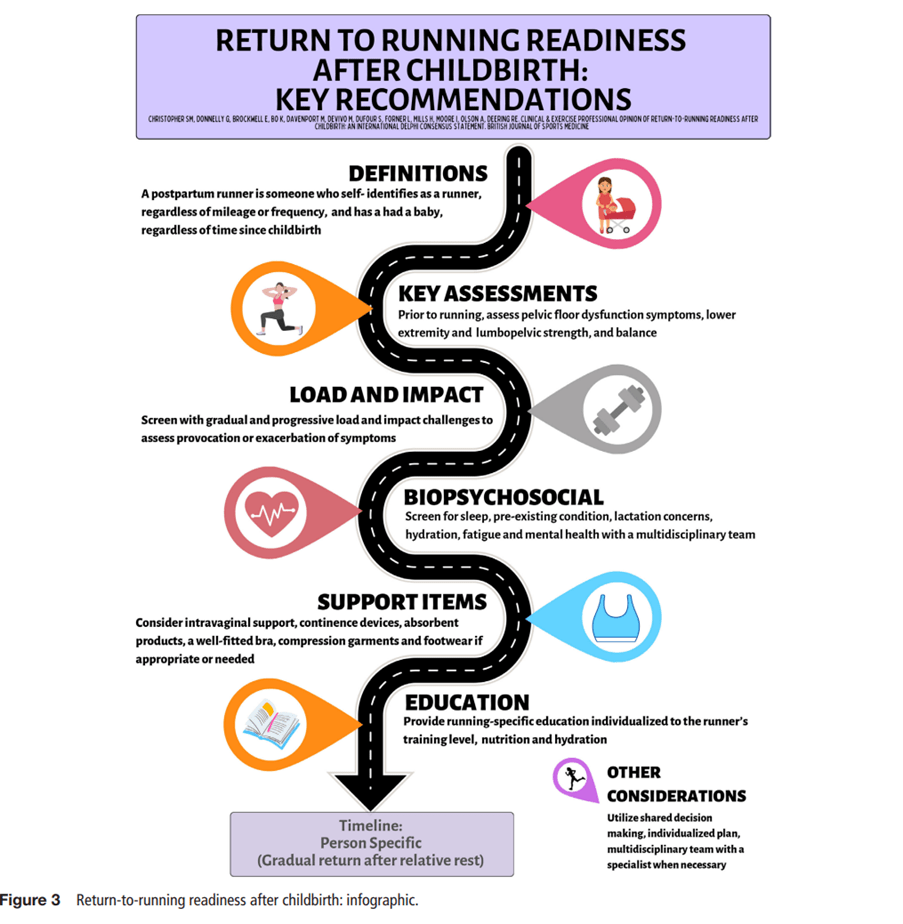

A Phased Approach to Returning to Running

Postpartum recovery is highly individual, but research recommends a gradual return to running. Deering et al. (2024) highlight that a structured approach reduces injury risk and improves long-term performance. Key milestones to assess readiness include:

- Minimum 3-week recovery period to allow for initial healing.

- No pain or pelvic floor symptoms (e.g., incontinence, pressure, or discomfort during impact activities).

- Ability to perform strength and impact tests, such as single-leg squats and hopping without discomfort.

Recommended Running Progression

- Phase 1 (Weeks 0-6 postpartum): Rest, walking, gentle core activation, and early pelvic floor training.

- Phase 2 (Weeks 6-12 postpartum): Strength training, low-impact activities (cycling, swimming), and brisk walking.

- Phase 3 (Weeks 12+ postpartum): Walk-run intervals, gradually increasing intensity and terrain complexity (Wyatt et al., 2024). Couch to 5K can really help here.

Deering et al. (2024)

A study involving 3,102 postpartum women found that 86% experienced musculoskeletal pain while running during pregnancy, particularly in the pelvis and lower back (Wyatt et al., 2024). These findings reinforce the importance of a phased return to prevent exacerbation of pain or injury.

Postnatal Assessments: Why a Mummy MOT Matters

One of the biggest challenges for postpartum runners is lack of guidance on when and how to return safely. While NICE guidelines (2021) recommend a GP check-up at 6-8 weeks postpartum, this is often insufficient for runners.

A Mummy MOT is a specialist postnatal assessment led by a women’s health physiotherapist that evaluates pelvic floor function, core stability, and movement mechanics (Deering et al., 2024). Key benefits include:

- Screening for diastasis recti (abdominal separation).

- Identifying pelvic floor dysfunction, reducing incontinence and prolapse risk.

- Providing individualized rehab plans, ensuring a safe return to high-impact activities like trail running.

Overcoming Common Barriers to Running Postpartum

Postpartum runners often face challenges such as limited access to professional guidance and misinformation about postnatal recovery. Social media can amplify these challenges. During a time when women are adjusting to a new reality and striving to maintain their sense of identity, it can become overwhelming and negatively impact their mental well-being.

Many women self-assess their readiness based on how they feel, which increases the risk of injury (Darroch et al., 2022). More education and awareness about evidence-based return-to-running strategies can help prevent setbacks and promote long-term success.

Another common barrier is musculoskeletal pain. Studies show that up to 86% of postpartum women experience pain while running, particularly in the pelvis and lower back (Wyatt et al., 2024). Strength training and gradual exposure to impact activities can significantly reduce these issues.

Final Thoughts

Returning to trail running postpartum is achievable with patience, strength training, and a phased approach. Prioritizing core stability, pelvic floor health, and gradual progression can help new mums rebuild confidence and strength while reducing the risk of injury. Investing in a Mummy MOT and following an evidence-based recovery plan will set the foundation for a strong, injury-free return to the trails.

Shefali et al. (2024)

References

Blyholder, L., Chumanov, E., Carr, K., & Heiderscheit, B. (2017). Exercise behaviors and health conditions of runners after childbirth. Sports Health, 9(1), pp.45–53.

Bø, K., Artal, R., Barakat, R., Brown, W. J., Davies, G. A. L., Dooley, M., Evenson, K. R., Haakstad, L. A. H., Kayser, B., Kinnunen, T. I., Larsén, K., Mottola, M. F., Nygaard, I., van Poppel, M., Stuge, B., & Khan, K. M. (2017). Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3—exercise in the postpartum period. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51, pp.1516–1525.

Darroch, F., Schneeberg, A., Brodie, R., Ferraro, Z. M., Wykes, D., Hira, S., Giles, A. R., Adamo, K. B., & Stellingwerff, T. (2022). Effect of pregnancy in 42 elite to world-class runners on training and performance outcomes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 55(1), pp.93–100.

Deering, R. E., Donnelly, G. M., Brockwell, E., Bø, K., Davenport, M. H., De Vivo, M., Dufour, S., Forner, L., Mills, H., Moore, I. S., Olson, A., & Christopher, S. M. (2024). Clinical and exercise professional opinion on designing a postpartum return to running training program: An international Delphi study and consensus statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 58, pp183–195.

Evenson, K. R., Mottola, M. F., Owe, K. M., Rousham, E. K., & Brown, W. J. (2015). Summary of international guidelines for physical activity following pregnancy. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 69(7), pp.407–414.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2021). Pelvic floor dysfunction: Prevention and non-surgical management (NG210). NICE Guidance. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng210

Shefali, C., Donnelly, G., Brockwell, E., Bo, K., Davenport, M., Vivo, M., Dufour, S., Forner, L., Mills, H., Moore, I., Olson, A. and Deering, R. (2024) Clinical and exercise professional opinion of return-to-running readiness after childbirth: an international delphi study and consensus statement. British Journal od Sports Medicine. 58. pp.299-312.

Wyatt, H. E., Sheerin, K., Hume, P. A., & Hébert‑Losier, K. (2024). Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal pain when running during pregnancy: A survey of 3102 women. Sports Medicine, 54, pp1955–1964.

Leave a comment